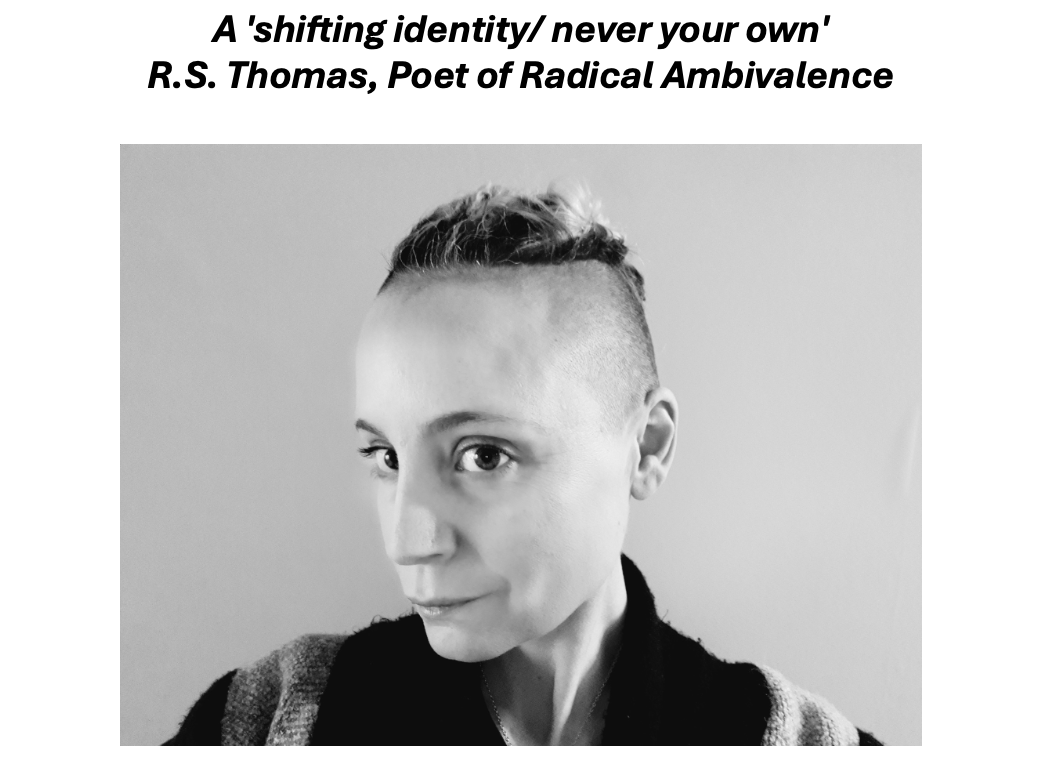

On 18th November, Fran Locke will give the Dyson lecture on R.S. Thomas.

This is one of a series of lectures endowed by former Pembroke student A.E. Dyson, literary critic, gay rights campaigner, educational activist and co-founder of the journal Critical Quarterly.

The title of her lecture is “A ‘shifting identity/ never your own’ R.S. Thomas, Poet of Radical Ambivalence.”

The lecture will take place at 5.30 in the Old Library, Pembroke college, drinks to follow.

All are welcome!

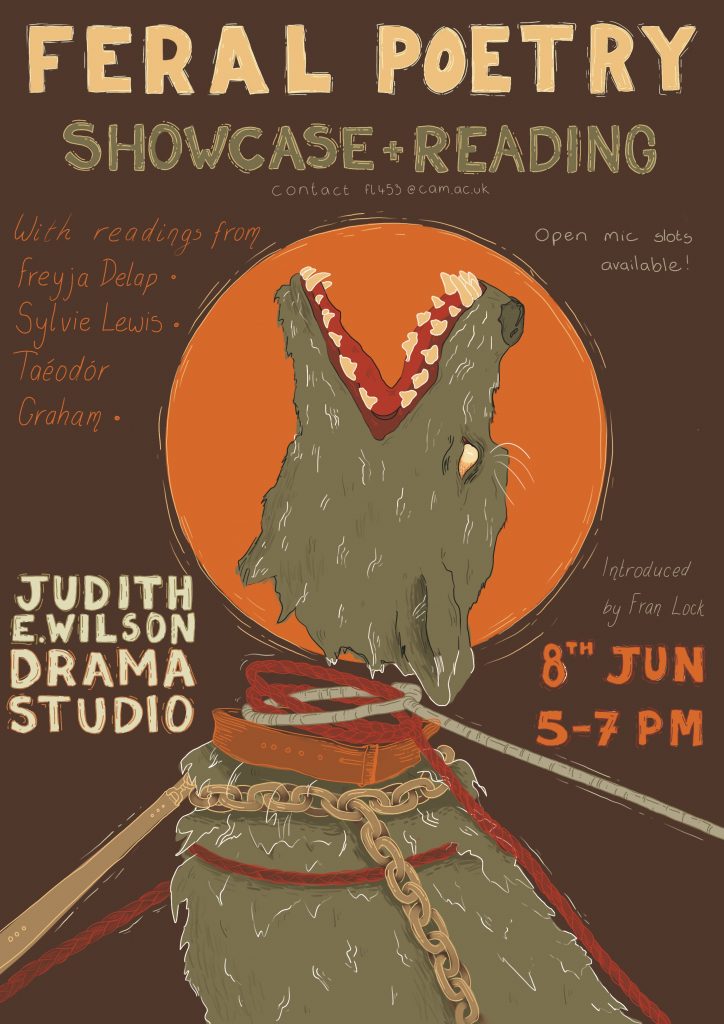

Fran Lock is the author of numerous chapbooks and fourteen poetry collections, most recently Hyena! (Poetry Bus Press, 2023), shortlisted for the T.S.Eliot Prize 2023, and ‘a disgusting lie’: further adventures through the neoliberal hell-mouth (Pamenar Press, 2023). Her most recent pamphlet is The New Herbal (Blueprint Press, 2024). Fran was the Judith E. Wilson Poetry Fellow at Cambridge University (2022-23), researching feral subjectivity through the lens of the medieval Bestiary. Vulgar Errors/ Feral Subjects, a collection of hybrid essays based on her work at Cambridge, was published by Out-Spoken Press last year. Fran is a Commissioning Editor radical arts and culture cooperative Culture Matters. She teaches at City Lit, and she edits the Soul Food column for Communist Review.

A ‘shifting identity/ never your own’ R.S. Thomas, Poet of Radical Ambivalence

The reputation of R.S. Thomas sine-waved wildly throughout his lifetime, with English critics in particular striving alternately to assimilate or to distance him from their conception of the national canon. The poet’s death in 2000 did little to stabilise these unwieldy oscillations, at the heart of which – enigmatic and implacable – stood the fractalised figure of Thomas himself, a tree ‘Without roots, but with many branches.’

Thomas was an ardent advocate of Welsh language and culture who wrote his characteristic poetry in English. He was an avowed pacifist who yet supported the violent direct action of the Meibion Glyndŵr group, which carried out arson attacks against English-owned holiday cottages in rural Wales. He was an Anglican priest whose poetry wrestled continually with an uncomfortably elusive – if not entirely absent – God. His work too proliferates images of uncertainty and estrangement, from nation, language, faith, community and self: ‘I am not one/ Of the public; I have come a long way/ To realise it.’

Ambivalence is not, in fact, merely a psychological state for Thomas, but a conscious and highly dynamic poetic strategy emerging from a radical anti-materialist ethics, and from his post-colonial situation. Drawing on Homi Bhabha’s notion of ambivalence and mimicry we can re-encounter Thomas as a Welsh poet using English to imitate, infiltrate and disrupt the British colonial literary norm. His work has the unsettling ability to reproduce inside of one language the tactics of another, provoking an uncanny feeling of two-fold cultural threat: threat to the integrity of the colonised subject, but also threat to the imperial power that strives to contain it.